A BILINGUAL PAGE TO COLLECT AND DISCUSS COMMENTS ABOUT FILMS, THEATER AND ART AND SOME POLITICS. ENGLISH/SPANISH

Monday, December 8, 2014

Saturday, October 11, 2014

THE INVISIBLE COLOR

As one of the founding fathers

of Afro-Cuban cinema, Sergio Giral is helping bring the black Cuban experience onto the screen. Karen Juanita Carrillo, bfm May/June 2006

1959

DOCUMENTARY STATEMENT

The Invisible Color documentary investigates the black Cuban

experience in United State and Miami Dade County in particular, since the first

wave of political refugees in the 1959 revolutionary aftermath to today, tracks

its presence throughout the region, and highlights its contribution to Miami’s

civic culture through testimonies and visual documentation.

1980

While any visitor to Cuba will notice the ubiquitous

presence of Afro-descendants everywhere, black Cubans are invisible in the

biggest Cuban enclave outside Cuba: South Florida. The Miami exile is white.

Although there was about a 10% of Cubans of color in the pre-1990s exile waves,

only a tiny fraction of them stayed in Miami, where non-white Cubans made only

a 2% of the total. The result is that the face of Cuban exile is white.

The Invisible Color

testimony the experience through the eyes of Black Cubans everyday life in

Miami Dade County in particular. Interviews, film clips, archive footage and

any possible media will be used to highlight our mayor occupations and

contribution to society as well life in contemporary Cuba. Members of the South

Florida community, Blacks and Whites, experts on the subject, artists, Scientifics

as well as everyday people will document the social and cultural aspects of

Black Cuban heritage. In sum, The Invisible Color will be more than just an

hour-long documentary on the role, identity and contributions of Black Cubans

in American popular culture have either acknowledged or ignore from a

historical as well as contemporary point of view.

Tuesday, September 9, 2014

The Cuban syndrome or what goes around comes around.

Por Sergio Giral

Toma 1:

Toma 1:

El periodo de la

república cubana trajo consigo una serie de atractivos emblemáticos que lo

caracterizaron como uno de los períodos más atractivos para el turismo internacional.

Una capital llena de emociones caribeñas de rasgos europeizantes y un África punzante. Los visitantes se movían

seguros y divertidos por las calles de la ciudad en busca de sus preferidos

platos existenciales, ya sea un bar americano, una barra criolla, un restaurant

gourmet, una fonda de chinos, un puesto de fritas, una prostituta barata, una

prostituta elegante, un guateque guajiro, un toque de santo o un puro cazador.

Se compraban artículos de piel de cocodrilos en las tiendas de El Prado y el

último grito de la moda francesa en El Encanto. Algunos viajaban al interior en

busca de la paz campesina y los románticos paisajes de un valle, una cascada,

un pueblo detenido en el tiempo y el espacio, montañas de aborígenes caribeños,

playas exclusivas, playas púbicas, un pase de coca, un suspiro de marihuana o

un simple saludable bienestar. La capital también albergaba celebridades

literarias, hollywoodenses, pintores y toda la fauna del arte contemporáneo del

momento. Los centros nocturnos empequeñecían

el recuerdo del cabaret alemán y se disputaban un espacio junto al Lido y al Moulin

Rouge. Luces, colores, mujeres de carnes firmes y la música. La música es el

talismán de la herencia cubana que permite romper los avatares más poderosos y

convertirlos en aliados. Música que escapa de instrumentos mujer y tambor africano.

Había más, los ciudadanos de la capital. Los ciudadanos de la

capital llevaban con orgullo su distintivo personal, ya sea racial, económico o

social. Los visitantes se movían en su espacio propio y casualmente eran

interferidos por limosneros y prostitutas de a pie. Un pueblo que no veía en el

visitante una ventaja, una solución, un respiro y un anhelo. Los ciudadanos se

movían en su propio espacio y así los visitantes.

Toma 2:

Sucedió que cansados de sus visitantes el pueblo se

enroló en una aventura xenofóbica y los arrojó del templo, los sustituyó por

campesinos barbudos y militantes arribistas. Luego vinieron los otros, los de

lejos, con un lenguaje nunca antes escuchado, costumbres nunca antes practicadas,

olores nunca antes percibidos. Esos nuevos visitantes no encontraron un bar americano, una barra criolla, un restaurant

gourmet, una fonda de chinos, un puesto de fritas, una prostituta barata, una

prostituta elegante, un guateque guajiro, un toque de santo. No se compraron

artículos de piel de cocodrilos en las tiendas de El Prado y el último grito de

la moda francesa en El Encanto. No viajaban al interior en busca de la paz

campesina y los románticos paisajes de un valle, una cascada, un pueblo

detenido en el tiempo y el espacio, montañas de aborígenes caribeños, playas

exclusivas, playas púbicas, un pase de coca, un suspiro de marihuana o un

simple saludable bienestar. No acudían a centros nocturnos de luces, colores,

mujeres de carnes firmes y la música. No lo encontraron ni lo buscaron porque

no existían y también porque no lo conocían. Los descendientes de Raskolnikov y

los Karamazovs se mantuvieron en ghettos especiales donde comían sus platos tradicionales,

bebían su alcohol tradicional, fumaban sus hierbas tradicionales y sobretodo no

se juntaban con los ciudadanos de la capital. Otros llegaron de El Sur en una

estampida huyendo del desprecio dictatorial para caer en otro desprecio dictatorial

que los protegió, alimentó, albergó, privilegió sobre los ciudadanos. Un día

todos se marcharon y la capital quedó derrumbada, agotada, incrédula, irreverente,

violada, machucada por los visitantes.

Toma 3:

Página en construcción.

Monday, September 1, 2014

THE INVISIBLE COLOR

The invisible color is a

living testimonial of the experience through the eyes of Black Cubans everyday

life in Miami Dade County in particular, highlighting their mayor occupations

and contribution to society as well their life in contemporary Cuba. Cubans and their descendants represent the largest demographic group of

Hispanic in South Florida, yet the Black Cubans has gone largely unnoticed due

to the Census have limited the reporting them as just as “Hispanic,” Without

specific data on Cubans of African descendants, it seems that the only way to

know the role of this invisible group plays in our society is to let our own

daily experience be the judge. Members of the South

Florida community, Blacks and Whites, Scholar, experts on the subject will

document the social and cultural aspects of Black Cuban heritage.

In sum, The Invisible

Color it's more than just an hour-long documentary on the role, identity and

contributions of Black Cubans in American popular culture have either

acknowledged or ignore from a historical as well as contemporary point of view.

Saturday, August 2, 2014

Tuesday, April 5, 2011

THE INVISIBLE COLOR

By Sergio Giral

Over decade Latino immigration have caused a major shift in the demographic complexion of Unites State. Caribbean, Central and South Americans are expanding and contributing to the social and cultural composition in the country. Among these growing group of Latinos who have played a significant role in this complexion are – the Black Latinos – who has gone largely unnoticed, not only to White and Black Americans, but also to Latino Americans whose own social structure historically has alienated them as a result of race. If we focus on the Black Latino experience, we will find that many immigrants and exiles had settled where topographical, cultural and language similarities afforded them the easiest opportunity for assimilation into U.S. society. Assimilation, however, proved more to difficult to attain for Black and mestizo, especially in a traditional racial social structure. However, by 1965, the United States’ history of slavery, segregation and racism was overcome by the achievements of its Civil Rights Movement. Focusing on Cuba’s experience, the first Cuban leap to Miami after Fidel Castro’s victory in late 1958 was wealthy and well-educated white elite who spoke English and slipped easily into Miami society. However, by 1965, the United States’ history of slavery, segregation and racism was superseded to by the achievements of its Civil Rights Movement. As a result, the potential for racial equality in the United States soon became a contributing factor in many Black Cubans’ decision to immigrate to the United States in the Mariel’s migration and the 1995 boatlift explosion preferable to cities like New York, where other Black Latinos groups had established a large and important presence. Popular culture may provide some insight, especially if we examine television – the epitome of an American popular culture. It is elementary to acknowledge that television’s publicity spots and commercials are targeted to attract consumers. And soap operas pursue ratings to accomplish sponsors investment, yet Latino TV producers avoid the Black subject, mimicking Hollywood on the 50’s when film studios cast Gina Lollobrigida, an Italian actress to play Queen of Sheba on “Salomon and Sheba” or in “Veracruz” where Sara Montiel, an Spaniard actress, plays the role of an American Indian girl, the possible closer look alike to an average American spectator.

Gina Lollobrigida in Solomon and Sheba Sara Montiel in Veracruz

This schematic tradition survive on the Latino media and suppresses the possibility of a love story where both characters are Black, a sitcom like “Meet the Browns” or a talk show led by a Latino Black anchor such as Oprah in the American TV network, or a Tyler Perry’s film “For Colored Girls”, just to cite some examples. Even Colombia and Brazil who have a large Black population and are great soap opera providers, Black characters are reserved for maids, chauffeurs and slaves or exceptionally with Tais Araujo in “Xica da Silva” a 1966 Brazilian soap opera where a Black actress played the leading role. Or taking the case of Cuba, with a Socialist regimen that presumes of abolishing racial discrimination where soap operas suffers a lack of Black actors in a country with a 60% of Black population approximately. But once again the absence of a Black identity (excluding sports and entertainment), appears to prove that Black Latinos are a non-existent consumer demographic group, and leads one to think that the group is viewed as largely insignificant or obviously invisible from days of slavery to their significance in contemporary American society.

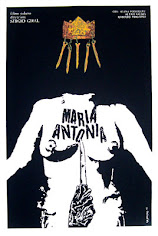

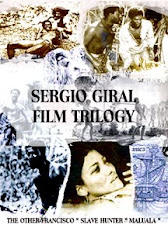

On my films I always have turn the camera point of view to the background, where slaves, maids and working class Black characters traditionally move along. From “The Other Francisco” that tells the impossible love story between two Black slaves; “Slaves Hunter”, “Maluala” and “Placido” that count the ordeal of Blacks and mestizos in search for freedom and equality in Cuba 19th. Century; “Maria Antonia” portraying the tragedy of a “mulata:” in Cuban Republican times; “Glass Roof” that denounces the privileges of white workers in a Socialist Cuba with a 60% of Black and mulatto population; to a more recent film “Two Times Ana” depicting the dreams and reality of a “colored” market cashier in Miami, my films have intended to contribute to unveil this invisible color on the screens.

Elvira Valdés in Two Times Ana 2011

Today seems hard to accomplish and to fill a void in the recording and reporting of the Black Latino experience as represented in both U.S. Census data and American popular culture as even Census data fails to accurately report upon the percentage of the count that was actually multiracial or specifically, Black Latinos. Without specific data on Latinos of African descendants, it seems that the only way to assess the role, which this invisible group plays in our society today, is let our own daily experience be the judge. The future of the Latino-American community depends on confronting the racial schisms that have been subordinated and denied for generations.

Lecture giving March 29th, 2011 at Markette University, Milwaukee, WI.

Thursday, August 4, 2011

THE INVISIBLE COLOR: A REVIEW OF OLD PAPERS.

By Sergio Giral

Over the last decades Hispanic immigration have caused a major shift in the demographic complexion of United State. In Miami-Dade County, this complexion is over 70% Hispanic -- with immigrants of Cuban descent making up the largest demographic, while an influx of Central and South Americans is both expanding and fragmenting the composition of Hispanics in the country. There is a growing group of Hispanics who have also played a significant role in this complexion – the Black Cubans – who has gone largely unnoticed, not only to White and Black Americans, but also to Hispanic Americans whose own social structure historically has alienated them as a result of race.

For a better understanding of this racial social structure, it is necessary to trace the history of Black Cubans from the days of the African slave trade to the Cuba. It is estimated that the number of slaves landing alive in Cuba over the whole period (1521-1870s) was over a million, almost one tenth of all slaves in the Americas. They were brought mostly in the 1800s. According to 1827 Census the Black and mulatto slaves and free came to compose approximately 60 % of the population while Whites, mostly from Spanish descendant a 40%.. The Haiti revolution in 1794, discourage whites Cubans to fight for independence from Spain and produced a campaign of fear “miedo al negro”, that was a determinative factor to delay the independence war until 1868, when the rest of Latin American countries were already freed.

Antonio Maceo

When Cubans began the Independence War against Spain, Black Cubans - free or slaves - strongly supported the revolt. Racial divisions and lack of unified leadership undermined these efforts until the rise of Independence heroes, the poet Jose Marti, and the mulatto liberator warrior, Antonio Maceo. For centuries, Black Cubans had played a recognized role in the struggle for independence in a truly multiracial term. The Cuban cigar workers, who arrived in Tampa from Key West in 1886, are an example of this historical continuity. About 15% of the Cuban population of Ybor City and West Tampa would be Black Cubans found them segregated from white Cubans, and separated by Black-Americans by language, culture and religion.

José Martí

During his stay in Ybor City, Jose Marti declared the necessity of a united front beyond racial differences to liberate Cuba from the colonial Spanish dominium, declaring that being Cuban was "more than white, more than black”. This alliance it’s proved by an incident in which Martí narrowly escaped poisoning by Spanish agents, and found protection and friendship under the roof of Ruperto and Paulina Pedroso, prominent Black-Cubans. For her aid to the cause, Paulina has been called the "second mother" to the apostle.

José Martí con tabaqueros cubanos en Tampa, Florida.

Patriotic organizations as Club Nacional Cubano founded by Jose Ramon Safeliz in 1890 and Sociedad la Union Marti-Maceo founded by Black-Cubans patriots in Tampa in 1900, were composed of whites and s members with not distinction of race, however, the group split along racial lines due to the pressures of the segregated South. Cubans in Ybor City and West Tampa suffered the consequences of Jim Crow Laws. When US retreated from Cuba and the island had its own constitution that included the Platt amendment, the new administration favored Spanish immigration pursuing to whitening the Island. Between 1900 and 1930 close to one million Spaniard arrived from Spain, and according to 1899 Census, Black and mestizo population decreased to 35%. Only a few outstanding Black-Cubans who distinguished themselves by very exceptional military abilities or Western educational standards had access to white privileged circles. Black Cubans usually worked in cane fields or as construction workers in urban areas, and almost always maintained low-income professions, which further deprived them of any social stay in Cuba.

Mariel boat lift to Miami

After Fidel Castro’s victory in late 1958, the first Cuban leap to Miami was wealthy and well-educated white elite who spoke English and slipped easily into Miami society. However, by 1965, the United States’ history of slavery, segregation and racism was superseded to by the achievements of its Civil Rights Movement. As a result, the potential for racial equality in the United States soon became a contributing factor in many Black Cubans’ decision to immigrate to the United States. Cubans living under a totalitarian regime have developed a system of survival for their physical and psychological needs according to what restrictions imposes the State. Consider well the Black population. For many years the Black Cubans in Cuba have been wrongly perceived by the exiled Cuban community as supporters of the Castro’s regime, due to significant given the recurrent myth that Fidel Castro has enhanced Cubans’ quality of life. Opposite to this believe, Black Cubans suffer discrimination and are considered alleged delinquents and drifters by the authorities. The penal population is almost exclusively Black. Currently, blacks and mulattos continue to be discriminated against in government leadership positions, even though they make up over half the population where only around 15 blacks hold seats in the 150-member Central Committee. Blacks and mulattos hold only six seats in Castro's military leadership and has practically no blacks in its ranks. Black Cubans have less access to dollars, since Cuban exiles that support their families in Cuba are predominantly white. These facts provoked a significant number of Black Cubans in the Mariel’s migration and the 1995 boatlift explosion. If we focus on Black Cuban experience, we will find that many Cuban exiles, and mestizo Cubans settled in South Florida where topographical, cultural and language similarities afforded them the easiest opportunity for assimilation into U.S. society. Assimilation, however, proved more to difficult to attain for Black and mestizo Cubans, especially in the traditional, racial social structure of South Florida and Miami-Dade County, in particular. To this end, many Black Cubans migrated to cities, like New York, where other Black Latinos groups had established a large and important presence.

Orlando Zapate Tamayo

The Cuban dissident movement has been also considered largely "white," with a few notable exceptions. However, Black and mestizo Cubans have played a significant role within the strong dissident movement in the Island. Among the many prisoners of conscience in Cuba, Jorge Luis Garcia Perez “Antunez” is an undeniable example of courage, suffering harassment and torture for his hunger strikes demanding Human Rights and political freedom. On February 2010, Orlando Zapata Tamayo, a Cuban Mason and political activist died in prison after fasting for more than 80 days. Guillermo Fariñas, an independent journalist who has been involved in a peaceful campaign for freedom of expression in Cuba, started a hunger strike that lasted 4 months calling for the release of prisoners of conscience. Fariñas was awarded the Andrei Sakharov Prize for Freedom of Thought by the European Parliament and Cuban authorities denied him the exit permit needed to travel outside the country. Dr. Oscar Elias Biscet, one of the 75 dissidents imprisoned in 2003 by the Cuban authorities, is a Black Cuban. Biscet was violently arrested and beaten while discussing a petition of Human Rights with16 other dissidents, condemned to 25 years sentence for "counter-revolutionary activities" and being kept in an infrahuman prison cell and finally freed in 2011. These bave dissidenets are Black Cubans.

Gina Lollobrigida as The Quenn of Sheba

Popular culture may provide some insight, especially if we examine television – the epitome of an American popular culture. It is elementary to acknowledge that television’s publicity spots and commercials are targeted to attract consumers. And soap operas pursue ratings to accomplish sponsors investment, yet Latino TV producers avoid the Black subject, mimicking Hollywood on the 50’s when film studios cast Gina Lollobrigida, an Italian actress to play Queen of Sheba on “Salomon and Sheba” or in “Veracruz” where Sara Montiel, an Spaniard actress, plays the role of an American Indian girl, the possible closer look alike to an average American spectator. This schematic tradition survive on the Latino media and suppresses the possibility of a love story where both characters are Black, a sitcom like “The Cosby Show”, “Meet the Browns” or a talk show led by a Latino Black anchor such as Wendy Williams, Tyra or Oprah in the American TV network, or a Tyler Perry’s film “For Colored Girls”, just to cite few examples. In the Latino soap operas Black and Native Latin American characters are reserved for maids, chauffeurs and slaves, exceptionally with Brazil who exceptionally portraits Black characters since Tais Araujo played the leading role in “Xica da Silva” a 1966 soap opera. Or taking the case of Cuba, with a Socialist regimen that presumes of abolishing racial discrimination where soap operas suffers a lack of Black actors in a country with a 60% of Black population approximately. Not to mention Mexico, with a 60% of mestizo population and none ethnic representation on the media.

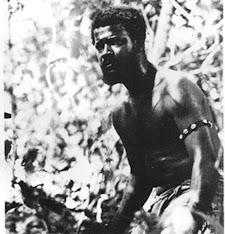

Samuel Claxton in Maluala

On my films I always have turn the camera point of view to the background, where slaves, maids and working class Black characters traditionally move along. From “The Other Francisco” that tells the impossible love story between two Black slaves; “Slaves Hunter”, “Maluala” and “Placido” that count the ordeal of Blacks and mestizos in search for freedom and equality in Cuba 19th Century; “Maria Antonia” portraying the tragedy of a “mulata:” in Cuban Republican times; “Glass Roof” that denounces the privileges of white workers in a Socialist Cuba with a 60% of Black and mulatto population; to a more recent film “Two Times Ana” depicting the dreams and reality of a “colored” market cashier in Miami, my films have intended to contribute to unveil this invisible color on the screens.

Celia Cruz a Black Cuban Idol

Due to today’s increasing of Blacks and mulattos in Cuba which possible could be compared to the 1836 Census, as a 51% mulatto (mixed white and black), 37% white, 11% black, and 1% Chinese, it’s difficult to assess the impact and role of Black Cubans in Miami Dade and South Florida from days of slavery to their significance in contemporary American society once Census data fails to accurately report upon them. In South Florida, for example, Hispanics represent 2.7 million, or 17% of Florida’s 15.9 million residents, but the 2000 census never reported on the percentage of the count that was actually multiracial or specifically, Black Cubans. Beginning with the 2000 Census, the federal government allowed people to choose more than one race. Until now, if a worker was Hispanic, reporting that worker's ethnicity was enough. The federal government now wants to know what race or races this Hispanic worker is. This even though the questionnaire, for the first time in its history, expanded the definition of race by allowing respondents to identify themselves with more than one race. In other words, the 2000 Census allowed for the counting of multiracial Hispanics, but limited the reporting of them as just “Hispanic.” Without specific data on Cubans of African descendants, it seems that the only way to assess the role, which this invisible group of Hispanics plays in our society today, is let our own daily experience be the judge. The future of Cuba and the Cuban-American community depends on confronting Cuban racial schisms that have been subordinated and denied for generations.

Labels: opiniones

Wednesday, June 18, 2014

Where we will be?

By Sergio Giral

Commonly racism and racial prejudice are result

slavery and colonial power. I yet in modern world it’s possible to find it

among the most developed societies.

Let’s take for an example United State long history on racism against

the African descendant. Without the intention of making an overview on a

subject who any civilized person knows nowadays, it’s simply to remind it. United

State no matter what racist law may appear on his constitution or presidential

periods, achieved to have an African-American president; that tells all.

Nevertheless the racial situation in Cuba has a long very shameful saga.

Without the intention, once more time, of telling historical facts beyond my

films on the subject and any civilized and cultured person may know, I feel the

need to approach Black Cubans in Cuba and in exiled.

Today the Cuba government struggle to survive out of

an economical and social crisis, result of Soviet Union collapse and the

paranoid megalomaniac Fidel Castro’s regime. Day after day flirt with United

State searching for new currents to modify anti Castro laws or at least to put

a band aid on internal unrest. Things have change since those days when a

regular Cuban couldn’t visit Miami to see his or her mother die or just to

receive an award or to collect any copyright charge. Since then, many things

have change. Today a new immigration law for Cubans allows a five years visa

and to remain in USA or six months on each travel. Good for Cubans whenever

they are.

Because a regular Cuban family in Cuba lacks on the

elemental resources to survive beyond what the regime offers them or what they can achieve in a complicated and absurd

parallel economy, which may include prostitution and or any other estimated bad

choices, Miami seems to be a key dream for solution. Maybe it’s right to show

the oppressed Cubans what a democracy can offer to any simple citizen by coming

to United State, to watch how American society has a millionaire Black woman

like Ophra and how one of the most successful celebrities like Kardashian marries a black man. That’s not the problem;

the problem is what is happening in Cuba with the Black population nowadays and

what it’s going to happen someday after the Castro regime falls. Have you ever thought of that?

In few of my previous post I had expressed my ideas

and consideration about the subject “Regardless the Cuban government promised

social achievements such as free education and free health care, Cuba

continuously fall down into economic crisis lower down white middle class into

the traditional Black population economical status, creating a false impression

of an egalitarian society. Cubans living under

a totalitarian have developed a system of survival for their physical and

psychological needs according to what restrictions are imposed the State.

Consider well the Black population”.

Friday, May 9, 2014

Black Int. Cinema Festival (2003) BERLIN. Award: best

film/video documentary production

Tuesday, April 29, 2014

SERGIO GIRAL FILM TRILOGY ON SLAVERY IN CUBA AND THE CARIBBEANS

On my films I always

have turn the camera point of view to the background, where slaves, maids and working class Black characters traditionally move along. From “The Other

Francisco” that tells the impossible love story between two Black slaves;

“Slaves Hunter”, “Maluala” and “Placido” that count the ordeal of Blacks and

mestizos in search for freedom and equality in Cuba 19th. Century;

“Maria Antonia” portraying the tragedy of a “mulata:” in Cuban Republican

times; “Glass Roof” that denounces the privileges of white workers in a

Socialist Cuba with a 60% of Black and mulatto population; to a more recent

film “Two Times Ana” depicting the dreams and reality of a “colored” market

cashier in Miami, my films have intended to contribute to unveil this invisible

color on the screens.

OTHER FANCISCO.

Cuba. 1974. 96 min.

A portray of the first

abolitionist novel in the Americas, “Francisco”, by Anselmo Suarez —written a

few years before the U.S. publication of “Uncle Tom’s Cabin”—to reveal the

realities of slavery in a parallel docudrama format in contrast to the romantic

depiction in the novel, the realities of slave rebellion are graphically and

consistently on the minds and in the hearts of enslaved Africans on Cuban

plantations. The film shows the cruelty to enslaved Africans while

deconstructing the narrative structures that underpin Suarez y Romero's

humanistic philosophy in segments of a historical exposé on the real conditions

of slavery in Cuba.

RANCHEADOR (Slave

Hunter)(95 min.), 1977

Rancheadores were slaves

hunters of the slave-owning colonialists in the Antilles charged with the task

of pursuing fugitive slaves and returning them to their owners. Getting paid

for his work by using the severed ear of a returned slave as proof of his

success. The film is based on the real story of Francisco Esteves, a

bloodthirsty rancheador, that not only hunted down runaways but as others of

his kind bolstered the power of the ruling class, cutting off the buds of

rebellion and thus liberty for all the oppressed, blacks and whites alike.

MALUALA (1980) 110

min.

A

tale of discord amongst the 19th Century African run-away slaves known as

"cimarrons". Shortly after overpowering their Spanish masters and

setting up secret “palanques” settlements in the mountains of eastern Cuba, the

cimarrons discover that there are traitors in their midst. The action takes

place during the last century in Maluala, the Black chieftain Gallo’s palenque,

together with his cohort, Coba, who present a petition for land and liberty if the

rebellious villages will be dismantled and their men offer themselves in

surrender. He promises that they will be freed shortly thereafter. Three

chieftains agree, but Gallo and Coba refuse. It is at this point that Spaniah

colonial government decides to use trickery and force in order to destroy the

Maluala community, to disrupt their hierarchy and gain total control. These

historical events which appear exotic and violent, but Giral constantly

implants into every image the necessity force to depict the actual facts.

Friday, March 28, 2014

A FILM PROJECT BY SERGIO GIRAL

BAREFOOT OVER BROKEN GLASSES

Synopsis:

Anthony,

a video journalist for a News Agency, obsessed with the memory of a woman,

thinks rediscover her while recording several personalities attending a

projection of photos of old mansions of Havana. Editing the video on his

computer blows up the woman’s image, freeze and print it. Trying to discover her

identity embarks on a journey with the different people who knew her in the

past and the reconstruction of the facts that did not allow her love.

Surprisingly

Elsa, the woman, appears to ask for the video and prevent its publication and regains

a passionate relationship where she does not remember having known him before.

Anthony tries to recover the video of his Chief Tom, who has a special interest

and entrusted him to continue searching for the real facts of the woman and her

husband. A dangerous journey in search of truth, muddle him through the

networks of a dictatorship. Haunted by the memory and reality finally Anthony

discovers the true identity of Elsa and allows publish the news that represents

an increase in publicity for the Agency and leads to a tragic end in the

woman's life.

RETRATRO DE UN ARTISTA INCONFORME

Por Sergio Giral

|

| Nestor Almendros |

.Conocí a Nestor

Almendros en 1958, mientras trabajabamos juntos como camareros en el café,

Playhouse, en la calle McDouglas, del Greenwich Village en New York. Hablábamos

de cine y nos hicimos buenos amigos, pero nunca llegué a sospechar que aquel

joven de acento español y seis pies de altura, fuera a ser uno de los

fotógrafos más importantes de la cinematografía internacional. Un artista

inconforme que buscó a lo largo de su vida un asidero a su espiritualidad y

valores humanos. Y uno de los personajes que más ha decidido en mi vida

artística

Nestor Almendros Cuyás

nació el 30 de octubre de, 1930 en Barcelona, España, el menor de tres

hermanos, en una familia de afiliación republicana. Los acontecimientos que

desataron el poder franquista en España, llevó a la familia Almendros al exilio

en la isla de Cuba, en 1948. Este fue el primer exilio de Nestor.

En la Habana, Nestor

formó parte de cine-clubs, y escribió criticas de cine, mientras estudiaba en

la Universidad. Sus contradicciones con el gobierno dictatorial de Batista y su

pasión por el cine le hicieron abandonar la isla y viajar a New York, donde

estudió edición cinematográfica en el New York's City College. Inquieto en su

constante búsqueda de la imagen en movimiento, regresó a Europa, para ingresar

en el Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia, en Roma, donde perfeccionó sus

experiencias como fotógrafo. Nestor veía al mundo através de un lente, pero no

de su cámara, sino de su propia naturaleza.

Regresa a New York y realiza

un corto de 8 minutos en 16 mm ya con títulos de crédito y la palabra FIN,

titulada "58-59", que vaticina el triunfo de la Revolución Cubana.

Esto movió a Nestor a regresar a Cuba, en busca de un posible sistema de

justicia social que su familia le inculcara desde niño. Lo que Nestor no

previó, fue la avalancha censora del sistema que ahogaría su espíritu creador.

Reencontré a Nestor en

1962, ya convertido en un director de fotografía profesional, produciendo sus

propios cortos en el Instituto de Cine Cubano (ICAIC). El reencuentro fue muy

fructifero, ya que me ofeció trabajar en el ICAIC donde yo pudiera llevar a la

práctica mi pasión por el cine. Así fue que ingresé en el ICAIC y comencé mi

carrera como cineasta, hasta mi partida definitiva de Cuba en 1991.

Durante su estancia en

Cuba Nestor rodó muchas películas informativas y documentales sobre proyectos

de gobierno, reforma agraria,higiene y educación. Junto a Tomás Gutiérrez

Alea realizó en 8mm "Una confusión cotidiana", y solo ayudado por su

hermano Sergio, "Gente en la playa", un delicioso "cinema

verite" de la playa popular La Concha con Vicentico Valdés en el sound

track. (este fue su pasaporte más tarde en el Cine europeo).

Nestor Almendros y Orlando Jiménez Leal

Nadie Escuchaba

La censura y prohibición

del los cortos PM, de Saba Cabrera Infante y Gente en la Playa, del propio

Nestor, por el gobierno cubano, engedraron contradicciones entre un grupo de

intelectuales y artistas con el régimen. Esto dió lugar al primer encuentro de

Fidel Castro con el mundo cultural de la Habana, y su lapidario discurso,

“Palabras a los Intelectuales”, donde definió la politica cultural del país:

“con la revolucion todo, contra la revolucion nada”. Estos hechos catapultaron

a Nestor fuera del la isla. Esta vez, para siempre. Nat Chediack,

que fuera director del Festival de Cine de Miami y amigo personal de Nestor

hasta sus ultimas horas, atestigua en en mi documental La Imagen Rota,

los tres exilios del artista.

Europa acogió a Nestor

nuevamente. Durante los años 60, Nestor colaboró con Eric Rohmer y Francois

Truffaut y otros cineastas de la Nueva Ola Francesa. Esta

reputación llevó a Nestor a Hollywood, la meca de del cine universal, que le

abrió sus puertas y le tendió una alfombra roja para su total desarrollo

artístico. El talento de Nestor finalmente obtuvo su merecido con un Oscar de

la Academia, por su fotografía en el filme de Terrece Malick, "Days of

Heaven", en 1978, donde perfeccionó su técnica de depender de

luz disponible a lo que él llamó "luz natural" y rodar con la luz

minutos previos a la puesta del sol, a la que llamó, "la hora

mágica, En una entrevista en Los Angeles Times 1978 mientras filmaba "Days of Heaven" definió su técnica "Como con el impresionismo, cuando los

tubos fueron inventados permitieron a los pintores ir al aire libre y atrapar la

luz natural." Otros filmes fotografiados por él, "Sophie

Choice", "Blue Lagoon" y "Kremer vs. Kramer", también

fueron nominados al premio de la Academia.

A lo largo de su carrera

cinematografica, Nestro Almedros, obtuvo premios internacionales. En

1980, gana el Premio Cesar de Francia, por su filme The Last Metro, de Francois

Truffaut. En 1982 plasmó sus experiencias cinematográfica en su libro

sobre fotografía de cine, “Un Homme a la Camera”. En 1984 fue condecorado en

Francia con la Legión de Honor Chevalier, orden de las artes y las letras

francesas, por su mayor obra como director, “Conducta Impropia”, una denuncia

sobre la persecusión de homosexuales por el gobierno de Castro. Más

tarde, coproduce y coescribe con el cineata Jorge Ulla, “Nadie Escuchaba”, que

expone la represión y las violaciones de los derechos humanos en Cuba.

La exitosa carrera de

Nestor fue tronchada por la epidemia del SIDA, que destruyó su organismo con un

cancer linfático. Fue entonces, durante su larga y dolorosa enfermedad,

que mi vida se vuelve a entroncar con la de Nestor. Después de un larga jornada

como director de cine en Cuba, llega el momento de la desiluisión, no tan

temprana como la de Nestor, pero al fin auténtica como la de él. Mis deseso de

salir de la isla y regresar a los EE,UU, hacen eco en sus oidos ya débiles por

la enfermedad, pero suficientemente receptivos para tenderme un nuevo puente

salvador de mi carrera cinematogrófica y mi libertad individual.

Nestro Almendros, muere

el 4 de marzo, de 1992 en la ciudad de New York.

Filmografía:

1967 La

Collectionneuse (Rohmer); The Wild Racers (Haller).

1969 More (Schroeder); Ma nuit chez Maud (My Night at Maud's)(Rohmer); L'Enfant sauvage (The Wild Child) (Truffaut)

1969 More (Schroeder); Ma nuit chez Maud (My Night at Maud's)(Rohmer); L'Enfant sauvage (The Wild Child) (Truffaut)

1970 Domicile

conjugal (Truffaut); Le Genou de Claire (Rohmer)

1971 Les Deux

Anglaises et le continent (Truffaut); La Vallée

(Schroeder)

1972 L'Amour

l'après-midi (Rohmer)

1973 Femmes au

soleil; The Gentleman Tramp (Patterson)

1974 La Gueule

ouverte (Pialat); General Idi Amin Dada (Schroeder); Cockfighter

(Hellman); Mes petites amoureuses (Eustache)

1975 L'Histoire

d'Adèle H. (Truffaut); (The Mistress) (Schroeder)

1976 Die

Marquise von O. (Rohmer); Des journées entières dans les arbres

(Duras); Cambio de sexo (Aranda)

1977 L'Homme qui

aimait les femmes (Truffaut); La Vie devant soi (Mizrahi); Beaubourg (Rossellini—doc); Koko (Schroeder—doc); Goin'

South (Nicholson)

1978 La Chambre

verte (Truffaut); Days of Heaven (Malick); Perceval

le Gaullois (Rohmer)

1979 L'Amour en

fuite (Truffaut); Kramer vs. Kramer (Benton); The

Blue Lagoon (Kleiser)

1980 Le Dernier

Métro (Truffaut)

1982 Still of

the Night (Benton); Sophie's Choice (Pakula); Pauline

à la plage (Rohmer);Vivement dimanche! (Truffaut)

1984 Places in

the Heart (Benton)

1986Heartburn (Nichols)

1987 Nadine (Benton)

1989 "Life

Lessons" ep. of New York Stories (Allen, Coppola and

Scorsese)

1990 Billy

Bathgate (Benton)

Friday, March 21, 2014

FADE TO BLACK

By Sergio Giral

In film making terminology Fade

to Black means just what it implies,

the disappearance of the image on

the screen until all colors become black leaving nothing but a black screen. Something

similar happens with Black Hispanics on television networks.

Latino immigration has caused

a major shift in the demographic complexion of United State, where Cubans have

gone to be the largest, living about 80% in Miami. Among these growing demography

are the Black Latinos, who have gone largely unnoticed, not only to White and

Black Americans, but also to Latino Americans whose own social structure

historically has alienated them as a result of race.

To this end, popular culture

may provide some insight, especially if we examine television – the epitome of

an American popular culture. It’s known that television’s publicity spots and

commercials are targeted to attract consumers and soap operas pursue ratings to

accomplish sponsors investment, yet Latino TV producers avoid the presence of the

Black talents on their programs. Let’s

take Miami for an example.

It's seldom when nor isolated to find Black performers, anchors and programs conductors in Miami Spanish networks. Yet sport, musicians and singers are exceptions. I have the experience to be invited to a TV program and asked if I'm a musician. Why not a philosopher, a politicians or a film director? It's clear the own network suffers from lack of Black talents.

In 1959, Fidel Castro

attacked the existing racial discrimination encouraging the idealistic view

that it was possible to forget about racism. The case was declared solved.

Since then, discussions and studies of race and racism providing an accurate

picture of racial divisions on the island have been officially silenced and

provoked for many years that any approach toward racial inequalities in Cuba

were considered shameful and unnecessary and finally a Taboo issue.

Regardless the Cuban

government promised social achievements such as free education and free health

care, Cuba continuously fall down into economic crisis lower down white middle

class into the traditional Black population economical status, creating a false

impression of an egalitarian society. Cubans

living under a totalitarian have developed a system of survival for their needs

according to what restrictions are imposed the State. Consider well the Black

population.

For

many years Blacks in Cuba were wrongly perceived as supporters of the Castro’s

regime, due to the myth of an improved quality of life. Opposite to this believe

Black Cubans suffer discrimination and are considered alleged delinquents and

drifters by the authorities. The penal population is almost

exclusively Black. Currently, blacks and mulattos continue to be discriminated against in

government leadership positions.

Focusing on Cuba’s exiled community,

the first leap to Miami was wealthy and well-educated white elite who spoke English

and settled in South Florida where topographical, cultural and language

similarities afforded them the easiest opportunity for assimilation into U.S.

society. Assimilation, however, proved

to be more to difficult for Black and mestizo

Cubans, especially in the traditional, racial social structure of South Florida

and Miami-Dade County, in particular.

Castro’s own propaganda about

social equality in Cuba and traditional racial discrimination in United States

accomplished Blacks Cubans fear to be exiled.However, by 1965, the United

States’ history of segregation and racism was superseded to by the achievements

of its Civil Rights Movement. As a

result, the potential for racial equality in the United States soon became a

contributing factor in many Black Cubans’ decision to immigrate to the United

States on the Mariel’s migration and the 1995 boat lift. To this end, many Black

Cubans migrated to cities like New York, where other Black Latino groups had

established a large and important presence.

Lately the significant

compositions of Black Cuban political dissidents visiting USA has produced

their presence on some Miami TV programs, proving the importance of this ethnic

group on social and political Cuban life. But once again the absence of Blacks

on regular programming appears to prove that Black Latinos and especially Black

Cubans are a non-existent in United States or are obviously insignificant in

contemporary American society.

It’s difficult to assess the

impact and role of Black Latinos in American society today, as even Census data

fails to accurately report upon them, allowed for the counting as “Hispanics”,

but limited the reporting their race or ethnic.

In South Florida, for example, 2010 census declare

75% Florida’s population to be white (57.9%

were Hispanic white) and the second largest ethnic group were Black or African

American at 16%, but never

reported on the percentage of the count that was actually multiracial or

specifically, Black Latinos. In other

words, without specific data on Latino African descendants seems hard to accomplish a recording

of the Black Latino and Black Cubans presence in U.S. Nevertheless Black Latinos and Black Cubans represent a demography minority

group in South Florida and especially in Miami, they have played an essential

cultural and social role in their nation’s history that should be recognized on

the American popular culture, avoiding them to Fade to Black on the small

screen.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

.jpg)