Tuesday, April 5, 2011

THE INVISIBLE COLOR

By Sergio Giral

Over decade Latino immigration have caused a major shift in the demographic complexion of Unites State. Caribbean, Central and South Americans are expanding and contributing to the social and cultural composition in the country. Among these growing group of Latinos who have played a significant role in this complexion are – the Black Latinos – who has gone largely unnoticed, not only to White and Black Americans, but also to Latino Americans whose own social structure historically has alienated them as a result of race. If we focus on the Black Latino experience, we will find that many immigrants and exiles had settled where topographical, cultural and language similarities afforded them the easiest opportunity for assimilation into U.S. society. Assimilation, however, proved more to difficult to attain for Black and mestizo, especially in a traditional racial social structure. However, by 1965, the United States’ history of slavery, segregation and racism was overcome by the achievements of its Civil Rights Movement. Focusing on Cuba’s experience, the first Cuban leap to Miami after Fidel Castro’s victory in late 1958 was wealthy and well-educated white elite who spoke English and slipped easily into Miami society. However, by 1965, the United States’ history of slavery, segregation and racism was superseded to by the achievements of its Civil Rights Movement. As a result, the potential for racial equality in the United States soon became a contributing factor in many Black Cubans’ decision to immigrate to the United States in the Mariel’s migration and the 1995 boatlift explosion preferable to cities like New York, where other Black Latinos groups had established a large and important presence. Popular culture may provide some insight, especially if we examine television – the epitome of an American popular culture. It is elementary to acknowledge that television’s publicity spots and commercials are targeted to attract consumers. And soap operas pursue ratings to accomplish sponsors investment, yet Latino TV producers avoid the Black subject, mimicking Hollywood on the 50’s when film studios cast Gina Lollobrigida, an Italian actress to play Queen of Sheba on “Salomon and Sheba” or in “Veracruz” where Sara Montiel, an Spaniard actress, plays the role of an American Indian girl, the possible closer look alike to an average American spectator.

Gina Lollobrigida in Solomon and Sheba Sara Montiel in Veracruz

This schematic tradition survive on the Latino media and suppresses the possibility of a love story where both characters are Black, a sitcom like “Meet the Browns” or a talk show led by a Latino Black anchor such as Oprah in the American TV network, or a Tyler Perry’s film “For Colored Girls”, just to cite some examples. Even Colombia and Brazil who have a large Black population and are great soap opera providers, Black characters are reserved for maids, chauffeurs and slaves or exceptionally with Tais Araujo in “Xica da Silva” a 1966 Brazilian soap opera where a Black actress played the leading role. Or taking the case of Cuba, with a Socialist regimen that presumes of abolishing racial discrimination where soap operas suffers a lack of Black actors in a country with a 60% of Black population approximately. But once again the absence of a Black identity (excluding sports and entertainment), appears to prove that Black Latinos are a non-existent consumer demographic group, and leads one to think that the group is viewed as largely insignificant or obviously invisible from days of slavery to their significance in contemporary American society.

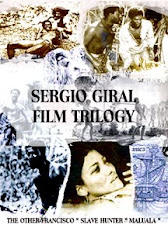

On my films I always have turn the camera point of view to the background, where slaves, maids and working class Black characters traditionally move along. From “The Other Francisco” that tells the impossible love story between two Black slaves; “Slaves Hunter”, “Maluala” and “Placido” that count the ordeal of Blacks and mestizos in search for freedom and equality in Cuba 19th. Century; “Maria Antonia” portraying the tragedy of a “mulata:” in Cuban Republican times; “Glass Roof” that denounces the privileges of white workers in a Socialist Cuba with a 60% of Black and mulatto population; to a more recent film “Two Times Ana” depicting the dreams and reality of a “colored” market cashier in Miami, my films have intended to contribute to unveil this invisible color on the screens.

Elvira Valdés in Two Times Ana 2011

Today seems hard to accomplish and to fill a void in the recording and reporting of the Black Latino experience as represented in both U.S. Census data and American popular culture as even Census data fails to accurately report upon the percentage of the count that was actually multiracial or specifically, Black Latinos. Without specific data on Latinos of African descendants, it seems that the only way to assess the role, which this invisible group plays in our society today, is let our own daily experience be the judge. The future of the Latino-American community depends on confronting the racial schisms that have been subordinated and denied for generations.

Lecture giving March 29th, 2011 at Markette University, Milwaukee, WI.

Thursday, August 4, 2011

THE INVISIBLE COLOR: A REVIEW OF OLD PAPERS.

By Sergio Giral

Over the last decades Hispanic immigration have caused a major shift in the demographic complexion of United State. In Miami-Dade County, this complexion is over 70% Hispanic -- with immigrants of Cuban descent making up the largest demographic, while an influx of Central and South Americans is both expanding and fragmenting the composition of Hispanics in the country. There is a growing group of Hispanics who have also played a significant role in this complexion – the Black Cubans – who has gone largely unnoticed, not only to White and Black Americans, but also to Hispanic Americans whose own social structure historically has alienated them as a result of race.

For a better understanding of this racial social structure, it is necessary to trace the history of Black Cubans from the days of the African slave trade to the Cuba. It is estimated that the number of slaves landing alive in Cuba over the whole period (1521-1870s) was over a million, almost one tenth of all slaves in the Americas. They were brought mostly in the 1800s. According to 1827 Census the Black and mulatto slaves and free came to compose approximately 60 % of the population while Whites, mostly from Spanish descendant a 40%.. The Haiti revolution in 1794, discourage whites Cubans to fight for independence from Spain and produced a campaign of fear “miedo al negro”, that was a determinative factor to delay the independence war until 1868, when the rest of Latin American countries were already freed.

Antonio Maceo

When Cubans began the Independence War against Spain, Black Cubans - free or slaves - strongly supported the revolt. Racial divisions and lack of unified leadership undermined these efforts until the rise of Independence heroes, the poet Jose Marti, and the mulatto liberator warrior, Antonio Maceo. For centuries, Black Cubans had played a recognized role in the struggle for independence in a truly multiracial term. The Cuban cigar workers, who arrived in Tampa from Key West in 1886, are an example of this historical continuity. About 15% of the Cuban population of Ybor City and West Tampa would be Black Cubans found them segregated from white Cubans, and separated by Black-Americans by language, culture and religion.

José Martí

During his stay in Ybor City, Jose Marti declared the necessity of a united front beyond racial differences to liberate Cuba from the colonial Spanish dominium, declaring that being Cuban was "more than white, more than black”. This alliance it’s proved by an incident in which Martí narrowly escaped poisoning by Spanish agents, and found protection and friendship under the roof of Ruperto and Paulina Pedroso, prominent Black-Cubans. For her aid to the cause, Paulina has been called the "second mother" to the apostle.

José Martí con tabaqueros cubanos en Tampa, Florida.

Patriotic organizations as Club Nacional Cubano founded by Jose Ramon Safeliz in 1890 and Sociedad la Union Marti-Maceo founded by Black-Cubans patriots in Tampa in 1900, were composed of whites and s members with not distinction of race, however, the group split along racial lines due to the pressures of the segregated South. Cubans in Ybor City and West Tampa suffered the consequences of Jim Crow Laws. When US retreated from Cuba and the island had its own constitution that included the Platt amendment, the new administration favored Spanish immigration pursuing to whitening the Island. Between 1900 and 1930 close to one million Spaniard arrived from Spain, and according to 1899 Census, Black and mestizo population decreased to 35%. Only a few outstanding Black-Cubans who distinguished themselves by very exceptional military abilities or Western educational standards had access to white privileged circles. Black Cubans usually worked in cane fields or as construction workers in urban areas, and almost always maintained low-income professions, which further deprived them of any social stay in Cuba.

Mariel boat lift to Miami

After Fidel Castro’s victory in late 1958, the first Cuban leap to Miami was wealthy and well-educated white elite who spoke English and slipped easily into Miami society. However, by 1965, the United States’ history of slavery, segregation and racism was superseded to by the achievements of its Civil Rights Movement. As a result, the potential for racial equality in the United States soon became a contributing factor in many Black Cubans’ decision to immigrate to the United States. Cubans living under a totalitarian regime have developed a system of survival for their physical and psychological needs according to what restrictions imposes the State. Consider well the Black population. For many years the Black Cubans in Cuba have been wrongly perceived by the exiled Cuban community as supporters of the Castro’s regime, due to significant given the recurrent myth that Fidel Castro has enhanced Cubans’ quality of life. Opposite to this believe, Black Cubans suffer discrimination and are considered alleged delinquents and drifters by the authorities. The penal population is almost exclusively Black. Currently, blacks and mulattos continue to be discriminated against in government leadership positions, even though they make up over half the population where only around 15 blacks hold seats in the 150-member Central Committee. Blacks and mulattos hold only six seats in Castro's military leadership and has practically no blacks in its ranks. Black Cubans have less access to dollars, since Cuban exiles that support their families in Cuba are predominantly white. These facts provoked a significant number of Black Cubans in the Mariel’s migration and the 1995 boatlift explosion. If we focus on Black Cuban experience, we will find that many Cuban exiles, and mestizo Cubans settled in South Florida where topographical, cultural and language similarities afforded them the easiest opportunity for assimilation into U.S. society. Assimilation, however, proved more to difficult to attain for Black and mestizo Cubans, especially in the traditional, racial social structure of South Florida and Miami-Dade County, in particular. To this end, many Black Cubans migrated to cities, like New York, where other Black Latinos groups had established a large and important presence.

Orlando Zapate Tamayo

The Cuban dissident movement has been also considered largely "white," with a few notable exceptions. However, Black and mestizo Cubans have played a significant role within the strong dissident movement in the Island. Among the many prisoners of conscience in Cuba, Jorge Luis Garcia Perez “Antunez” is an undeniable example of courage, suffering harassment and torture for his hunger strikes demanding Human Rights and political freedom. On February 2010, Orlando Zapata Tamayo, a Cuban Mason and political activist died in prison after fasting for more than 80 days. Guillermo Fariñas, an independent journalist who has been involved in a peaceful campaign for freedom of expression in Cuba, started a hunger strike that lasted 4 months calling for the release of prisoners of conscience. Fariñas was awarded the Andrei Sakharov Prize for Freedom of Thought by the European Parliament and Cuban authorities denied him the exit permit needed to travel outside the country. Dr. Oscar Elias Biscet, one of the 75 dissidents imprisoned in 2003 by the Cuban authorities, is a Black Cuban. Biscet was violently arrested and beaten while discussing a petition of Human Rights with16 other dissidents, condemned to 25 years sentence for "counter-revolutionary activities" and being kept in an infrahuman prison cell and finally freed in 2011. These bave dissidenets are Black Cubans.

Gina Lollobrigida as The Quenn of Sheba

Popular culture may provide some insight, especially if we examine television – the epitome of an American popular culture. It is elementary to acknowledge that television’s publicity spots and commercials are targeted to attract consumers. And soap operas pursue ratings to accomplish sponsors investment, yet Latino TV producers avoid the Black subject, mimicking Hollywood on the 50’s when film studios cast Gina Lollobrigida, an Italian actress to play Queen of Sheba on “Salomon and Sheba” or in “Veracruz” where Sara Montiel, an Spaniard actress, plays the role of an American Indian girl, the possible closer look alike to an average American spectator. This schematic tradition survive on the Latino media and suppresses the possibility of a love story where both characters are Black, a sitcom like “The Cosby Show”, “Meet the Browns” or a talk show led by a Latino Black anchor such as Wendy Williams, Tyra or Oprah in the American TV network, or a Tyler Perry’s film “For Colored Girls”, just to cite few examples. In the Latino soap operas Black and Native Latin American characters are reserved for maids, chauffeurs and slaves, exceptionally with Brazil who exceptionally portraits Black characters since Tais Araujo played the leading role in “Xica da Silva” a 1966 soap opera. Or taking the case of Cuba, with a Socialist regimen that presumes of abolishing racial discrimination where soap operas suffers a lack of Black actors in a country with a 60% of Black population approximately. Not to mention Mexico, with a 60% of mestizo population and none ethnic representation on the media.

Samuel Claxton in Maluala

On my films I always have turn the camera point of view to the background, where slaves, maids and working class Black characters traditionally move along. From “The Other Francisco” that tells the impossible love story between two Black slaves; “Slaves Hunter”, “Maluala” and “Placido” that count the ordeal of Blacks and mestizos in search for freedom and equality in Cuba 19th Century; “Maria Antonia” portraying the tragedy of a “mulata:” in Cuban Republican times; “Glass Roof” that denounces the privileges of white workers in a Socialist Cuba with a 60% of Black and mulatto population; to a more recent film “Two Times Ana” depicting the dreams and reality of a “colored” market cashier in Miami, my films have intended to contribute to unveil this invisible color on the screens.

Celia Cruz a Black Cuban Idol

Due to today’s increasing of Blacks and mulattos in Cuba which possible could be compared to the 1836 Census, as a 51% mulatto (mixed white and black), 37% white, 11% black, and 1% Chinese, it’s difficult to assess the impact and role of Black Cubans in Miami Dade and South Florida from days of slavery to their significance in contemporary American society once Census data fails to accurately report upon them. In South Florida, for example, Hispanics represent 2.7 million, or 17% of Florida’s 15.9 million residents, but the 2000 census never reported on the percentage of the count that was actually multiracial or specifically, Black Cubans. Beginning with the 2000 Census, the federal government allowed people to choose more than one race. Until now, if a worker was Hispanic, reporting that worker's ethnicity was enough. The federal government now wants to know what race or races this Hispanic worker is. This even though the questionnaire, for the first time in its history, expanded the definition of race by allowing respondents to identify themselves with more than one race. In other words, the 2000 Census allowed for the counting of multiracial Hispanics, but limited the reporting of them as just “Hispanic.” Without specific data on Cubans of African descendants, it seems that the only way to assess the role, which this invisible group of Hispanics plays in our society today, is let our own daily experience be the judge. The future of Cuba and the Cuban-American community depends on confronting Cuban racial schisms that have been subordinated and denied for generations.